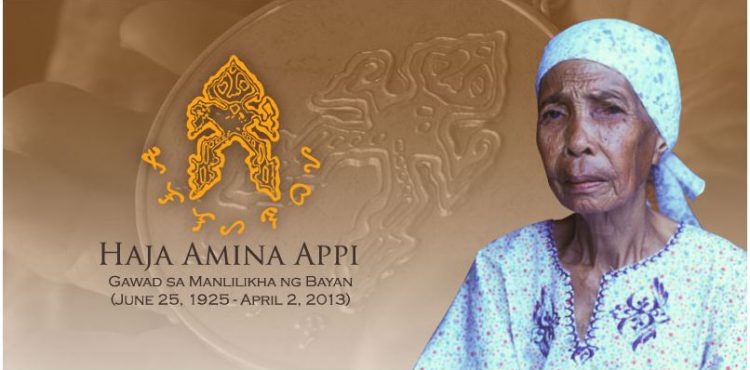

Haja Amina Appi

Mat Weaver

(Born: 25 June 1925)

Tawi-Tawi

Haja Amina Appi of Ungos Matata, Tandubas, Tawi-Tawi, is recognized as the master mat weaver among the Sama indigenous community of Ungos Matata. Her colorful mats with their complex geometric patterns exhibit her precise sense of design, proportion and symmetry and sensitivity to color. Her unique multi-colored mats are protected by a plain white outer mat that serves as the mat’s backing. Her functional and artistic creations take up to three months to make.

The art of mat weaving is handed down the matrilateral line, as men in the Sama culture do not take up the craft. The whole process, from harvesting and stripping down the pandan leaves to the actual execution of the design, is exclusive to women. It is a long and tedious process, and requires much patience and stamina. It also requires an eye for detail, an unerring color instinct, and a genius for applied mathematics.

The process starts with the harvesting of wild pandan leaves from the forest. The Sama weavers prefer the thorny leaf variety because it produces stronger and sturdier matting strips. Although the thorns are huge and unrelenting, Haja Amina does not hesitate from gathering the leaves. First, she removes the thorns using a small knife. Then, she strips the leaves with a jangat deyum or stripper to make long and even strips. These strips are sun-dried, then pressed (pinaggos) beneath a large log. She then dyes the strips by boiling them for a few minutes in hot water mixed with anjibi or commercial dye. As an artist, she has refused to limit herself to the traditional plain white mats of her forebears but experimented with the use of anjibi in creating her designs. And because commercial dyes are often not bold or striking enough for her taste, she has taken to experimenting with color and developing her own tints to obtain the desired hues. Her favorite colors are red, purple and yellow but her mats sometimes feature up to eight colors at a time. Her complicated designs gain power from the interplay of various shades.

Upon obtaining several sets of differently-colored matting strips, she then sun dries them for three or four days, and presses them again until they are pliant. Finally, she weaves them into a colorful geometric design. Instead of beginning at the outermost edges of the mat, she instead weaves a central strip to form the mat’s backbone, then works to expand the mat from within. Although the techniques used to make the mats are traditional, she has come up with some of her own modern designs. According to Haja Amina, what is more difficult than the mixing of the colors is the visualization and execution of the design itself. It is high precision work, requiring a mastery of the medium and an instinctive sense of symmetry and proportion. Despite the number of calculations involved to ensure that the geometric patterns will mirror, or at least complement, each other, she is not armed with any list or any mathematical formula other than working on a base of ten and twenty strips. Instead, she only has her amazing memory, an instinct and a lifetime of experience.

Haja Amina is respected throughout her community for her unique designs, the straightness of her edging (tabig) and the fineness of her sasa and kima-kima. Her hands are thick and callused from years of harvesting, stained by dye. But her hands are still steady, and her eye for color still unerring. She feels pride in the fact that people often borrow her mats to learn from her and copy her designs.

Happily, mat weaving does not seem to be a lost art as all of Haja Amina’s female children and grandchildren from her female descendants have taken it up. Although they characterize her as a patient and gentle teacher, Haja Amina’s passion for perfection shows itself as she runs a finger alongside the uneven stitching and obvious patchwork on her apprentices’ work. She is eager to teach, and looks forward to sharing the art with other weavers.

Source: Maricris Jan Tobias